The central tenet of the

Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy

is to preserve rural, agricultural, conservation, and recreational lands. All

municipalities in our region agree to this central tenet. Our region

implements this central tenet through the Urban Containment Boundary.

|

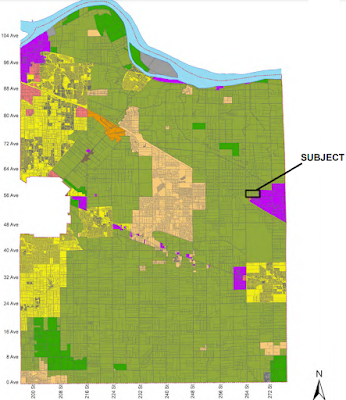

|

Metro Vancouver Urban Containment Boundary. Select the map to enlarge.

|

Having an Urban Containment Boundary protects local food production, reduces

greenhouse gas emissions and energy use from transportation, help sequesters

carbon by maintaining greenspace, and encourages the co-location of housing,

jobs, and services in walkable, bikeable, and transit-accessible

neighbourhoods. For local governments, it also reduces the cost of providing

services, meaning lower property taxes over the long term. The Urban

Containment Boundary prevents sprawl.

Because of the importance of the Urban Containment Boundary, if a local

government wants to adjust it, it requires the support of a two-thirds

weighted vote of the Metro Vancouver Regional District Board (made up of

representatives from Tsawwassen First Nation and all municipalities.) There

are some exceptions.

Our region has an

industrial land shortage. Industrial lands are important for our region. Point in case, while

industrial land is only four percent of the region’s land base, over 25

percent of jobs are on industrial lands.

Industrial lands are also regionally designated and protected. Changing from

industrial land use to another land use requires a 50%+1 weighted vote of the

Metro Vancouver Regional District Board. This vote is a barrier to converting

industrial land to other uses, though the barrier is lower than changing the

Urban Containment Boundary.

Interestingly, there is a shortcut for growing the Urban Containment Boundary

in the current version of our Regional Growth Strategy and the previous

version. You can convert land next to the Urban Containment Boundary to

industrial land with only a 50%+1 weighted vote of the Metro Vancouver

Regional District Board, not a two-thirds weighted vote.

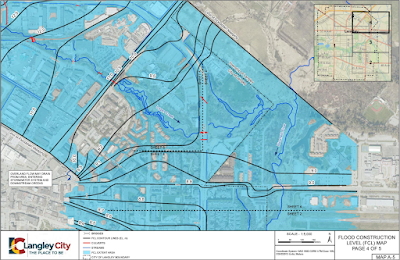

This shortcut is playing out near Gloucester Industrial Park in the Township

of Langley, where the

Township has an application with the Metro Vancouver Board

to change 14.59 hectares of regionally designated agricultural land to

industrial land.

|

|

Location of Conwest Group lands near Gloucester Industrial Park pending

Metro Vancouver Board vote to convert to industrial land. Select the map

to enlarge. Source: Township of Langley

|

Most agricultural land in Metro Vancouver is within the Agricultural Land

Reserve, which the provincial

Agricultural Land Commission

controls. The proposed conversion of this 14.59 hectares of land started with

Agricultural Land Commission exclusion requests from 2006, 2010, and 2020.

While the Commission denied

the 2006 and 2010 requests,

the 2020 request

for exclusion was successful. This exclusion is what allowed the current

regional request.

As noted by regional district staff, this land will help grow the industrial

land base constrained in this region. The land is near a major highway and

railway corridor.

On the other hand, Gloucester Industrial Park is only accessible by private

automobiles and is surrounded by the Agricultural Land Reserve. Expansion of

that area will increase vehicle kilometres travelled and greenhouse gas

emissions. It will also put pressure to exclude further land from the

Agricultural Land Reserve. Converting rural lands to industrial use can

encourage sprawl.

In the recent past, this played out with

South Campbell Heights

in Surrey, with former agricultural land converted to employment lands and

growing the Urban Containment Boundary.

Expanding the Urban Containment Boundary at two locations will not degrade

regional growth policies in Metro Vancouver when viewed in isolation. Still,

the cumulative effects of changing the Urban Growth Boundary over time degrade

regional growth policies and objectives.

In this post, I’m not speaking for or against the changes proposed near

Gloucester Industrial Park or the change that occurred in South Campbell

Heights in Surrey. I want to raise awareness that, as a region, there is now a

trend of converting former agricultural and rural lands for employment and

industrial uses. If this is the new normal for our region, we may want to

consider how we integrate these new employment and industrial areas into the

broader regional planning context of Metro Vancouver on how they can still

support addressing climate change and creating compact centres connected by

high-quality transit.